3: Concerning Mechs

Thoughts about large robots and their importance to humans.

7/25/20247 min read

Why always mechs? Why have them? Why do we like them?

In philosophic thinking this might be asserted to be an axiological question; a question about aesthetics and ethics. A question that splinters to things akin to asking what we mean by ‘like’ (aesthetics) or asking questions about expressing our love and admiration through purchasing commodities (ethics).

So, the notion of this post is trying to understand the general appeal of mecha. This is less a post about Electrocosmic and more of a post about the concepts that go into the game – given that the game’s typical focus is mechs, it’s worth sitting down to ask some questions about mechs and think about them a little. Simply stating ‘they’re big’ and ‘they’re cool’ seems insufficient to me, particularly when one tries to understand the persistence of the genre and the popular imagination of these peculiar things.

As such post is more of a series of assertions and thoughts on the matter rather systematic, though if one is willing to admit scattered thoughts or fragments of cultural artefacts. If this all has a thesis it will be roughly the following:

1. Mecha are a prosthesis for the human body and their odd form and nature is always in relation to the human.

2. Mecha are common cultural formation owing to time at which we live. As perception has changed to the subject these are to be expected as a natural product owing to subjectivity and the twists in the subject, the encroach of modernity, and the disenchantment of the world ala Weber.

This is not easily proved in a blog post. I mean, not really, but friend reader doesn’t have time for the entirety of the argument and a long-winded argument for it, I’m sure. Just the meat. So it will come in the form of a series of assertions which aren’t amazingly well formulated, so, I would ask friend reader to be charitable.

So, giant robots. It’s worth thinking about, especially when one writes fiction. Or, hypothetically, if the writer was dealing with a game of roughly the same genre – and Electrocosmic is in the same genre with the same basic material.

I suppose when I say mechs I mean large robots that are piloted rather than autonomous. They typically have two arms, two legs, and a head. They are anthropic and they have a weapon or something of that sort. While others might exist, the truth of the matter is that this basic form-factor holds despite attempts to modify it – there are few crawlers, hoverers, or millipede-style mechs.

These mechs also fight, usually. Again, if all of this seems obvious, it is because I am trying to start with the most basic assumptions in the same way a carpenter begins to tear into a wall: sheetrock, nails, wood, foundation, and so on.

Anyway, they fight. They are overwhelming things that fight rather than other things, though on occasion they deal in non-combat activity as in properties like Battletech. They are also typically linked with their pilot in some fashion, either in terms of friendship, destiny, maternal qualities, or narrative contrivance.

Even with such fingers on the scale to allow their usage in narrative is worth commenting on as I think it says something about them. The basic notion is that their basic form is indispensable, not for pragmatic reasons, but for the fact of deep human needs rooted in psychology.

To reiterate, though, as machines of war they’re not the first choice, if they are a choice at all. They are exposed and visible. They’re too costly to manufacture. They’re too large. They’re unstable. They fall over. They require enormous volumes of power. They’re impractical. There’s better weapon systems that have all of the advantages and none of the costs. The designs are silly, impractical, odd, or simply pointless. Everything that they do with another weapon system can do better – battleship guns, long-range missiles, aircraft-fired missiles, tanks, and so on.

This has been the argument. It holds, if one accepts the basic assumptions that are assumed in the form of the world in question, the physics, the basic presuppositions. To overcome it requires a bit of creativity or a bit of twisting in that the artist or the writer to torture the world’s axiomatic to make them work or give them some reason. As a behavior this might be said to be curious as the, the human mind’s logic and power is put to justification rather than more stale mimesis.

Not using such mechs is, however, obvious in the architecture of modernity. They are power-hungry monsters that make no sense and would never be adopted, but this sort of pragmatism has in whole, or part given modernity something of a strange taste if one considers the flavors. One might consider the aura of heroic wars of the past and the features of chivalry have crumbled under the weight of technological change with modern war being an increasingly horrifying inhuman enterprise. How many times have individuals complained about all the sport of it being ruined? All the skill being bled out of it? All the glory being diminished, and the human found being dragged by their own machine? I suppose this is why the cage comes up so much in Max Weber – the iron cage of rationality is the same basic fear that Eowyn has in Lord of the Rings.

Anyway, I think this is all worth considering. The mecha is in this fashion kind of a retrograde thing in that the human is required but also pushes against just machines. The person controls of the machine, and the machine seems to get a charm back. A sort-of- attempt to return the ‘fun and neat’ to what is roughly a bean-counter’s computerized warfare.

Mecha are more in their effect rather than their practicality in this. They absolve the human body of weakness and express some basic insecurity that doesn’t easily see much time outside the shadowed parts of the psyche. There’s a certain anxiety about these machines, they embody modernity, and humanity controls them – for now – only by the efforts of a select few – but society lives in their shadow as they live in the shadow of other machines.

Cars. Consider cars and how we live in the shadow of cars. Consider that most basic thing but seemingly terrifying, the car. The bog-standard car is not too dissimilar to a mech with respect to prosthesis and its effect on the world. We bend to the car’s demands and we feel compelled by it, but this car has an effect on us in the same fashion Marshall McLuhan or Mumford would recognize.

It occurred to me while I was walking one day. I stepped into the crosswalk and a woman in an SUV didn’t stop, period, and simply had a nonchalant confidence as she drove her huge wasteful thing around and did not concern herself for my weak pliable flesh. By accident she could have easily destroyed me with her tons of speeding metal. By accident.

This is merely an anecdote, but the popular wisdom is that women love these things, SUVs. Indeed, I noticed that, without fail, women preferred sport utility vehicles. I wondered why that was, or if my observations were accurate or if I would need a chart.

Still, from this the notion struck me about the SUV. It is large. It is also a commodity. Women as a whole feel less safe in society with the response being a downstream effect of commodity response – in this case larger vehicles, imposing vehicles, and so on. Another example of this behavior might be the typical ‘man with small penis’ car, where a man buys an exceedingly expensive vehicle to illustrate his status or absolve him on some corporeal weakness. The weakness of the flesh is solved by technological prosthesis, but one finds enslaved by the machine’s demands – gasoline, insurance, parts, maintenance, storage…

But the weakness and the prosthesis is where it is key, I think. The car is a mech and the mech is a car. I suppose this might seem sensible as so much of modern technology organizes itself around catering to human weakness, deficiency, physical issues, and so on. Most technology does; where the human fails they must devise a scheme with their mind, and these schemes are legion in the same fashion human weaknesses are legion.

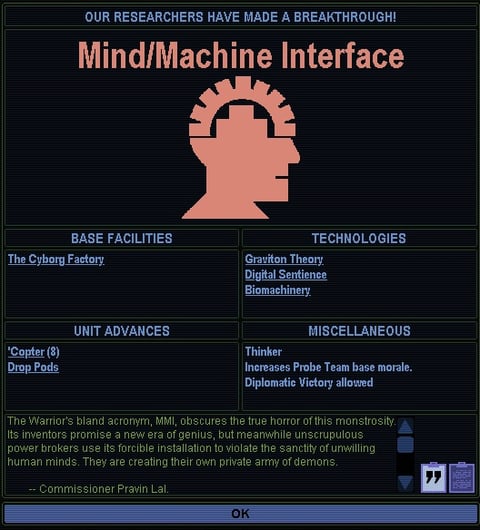

Which I suppose is the mecha’s appeal, worldwide. Big thing make small feel big cool and tough. One can control it in the same fashion as one controls a body, and it is effectively a body but largely void of pain. Although, as a prosthesis of the body there is more there – how much media involves connecting to the machine, fusing to the machine, having it linked to the brain, having it be penetrated-lanced-insinuated into the brain? It even has its own specie of tropes:

I don’t think there’s any country or nation-state that doesn’t have some love of mechs and their basic qualities. The constant appeal and desire to deal with the issues of the flesh and one’s own mortal shortcomings will seemingly never end, but the shadow of modernity has produced odd fruit in these comically large and amusingly impractical machines.

Impractical, it is true, but they serve some basic need in humans. Some sense of majesty. Some sense of nobility and honor. Some sense of skill and talent. Something retrograde, despite being highly advanced and often – in fiction – being the pinnacle of science.

In closing I should probably state how all of this ties to Electrocosmic else it comes off mild babble. As a setting and a system it attempts, in using alt-history and exploring some unusual ideas, to try to get some wiggle room in the setting for stranger or more unusual weapons, systems, ideas, and political ideas. Although it takes many cues from other settings and the genre, the attempt to roll back the clock and bend the arrows is the goal of the setting: with no real cold war to speak of and vast differences in the world experimental systems and other strange things can be snuck in or used without seeming out of place. This is a function requirement of the system as well as a personal quality of my own taste: although enjoying many of the stranger cold-war era vehicles, many of them can’t be justified or they are vastly outdated or aren’t used. However, because of the world’s basic metaphysics many now can be used – in addition to large mechs, which are fun, enjoyable, and symbolic – if not exactly, sensible.

© Austere Patio Games, 2024. All rights reserved.