5: Utopianism Themes and The Player

How does design impact player action in TTRPGs?

8/16/20245 min read

I thought I would bring up the issue of utopian thinking with respect to cosmic horror and the player.

This is mostly because I don’t think the issue has been broached in articles I’ve read. It also allows some clarity about Electrocosmic’s conceptual base, influences, and my thinking on the game’s setting and design.

The Bathtub of Moral Action

It’s also something I’ve chosen to consider, mostly since other mecha RPGs – particularly Lancer – deals in utopian themes. However, the basic question remains in that why the basic better world notions that pile in with utopian settings has lost so much ground to the darker futures of cyberpunk and post-apocalyptic settings, themes, and so on.

Why this is important is roughly thus: When designing and conceptualizing TTRPG games the tone serves to organize player behavior, motivations, interests, ideas, and so on. Try to think of it like a bathtub: understanding the scale, shape, angles, and texture of the basin greatly serves to enframe player action and what they desire to do, can do, etc. It constrains the boundaries of understanding, self-concept, and so on – when in Rome, as the saying goes.

Perhaps an example. For instance, a group of pilots ala Armored Core: Fires of Rubicon would be scavengers of self-interested mercenaries, while a group of pilots in Lancer are typically agents of Union that are, at least in principle, interpreted as heroic or morally laudable. Comparatively, Armored Core is typically more morally rootless: the mercenary is often depicted as a ‘gray area’ character despite their less than obvious neutrality – though in Japanese media this is something of a trope that does not peg to the general opinion of actual mercenaries.

Lancer has different problems, though when playing Armored Core there’s no doubt about the morality of the player character; They are merely a prosthesis for the vague morality of the player’s actions and have no real morality underneath. Comparatively, mercenaries in a more western context implies a rootless evil, maliciousness, or casual brutality.

Anyway, Lancer’s issue is roughly that. The results of the design of Lancer has yielded a few comments owing to the above; For instance, it is, as a setting, interpreted by some as thematically muddled: although the future state of Union is at the edge of post-scarcity pseudoutopia it is still at war with other states and beset by reactionary or backward elements. While this is reasonable enough at a glance it is beset by what I might call the ‘Federation Problems’; despite being a nominal paradise, the Federation of Planets in Star Trek is forced to, by matter of necessity, engage with the following problems that cannot be (easily) handwaved away:

It must endure less ideologically palatable alternatives to their administration, such as Cardassians or Romulans or Ferengi.

It must consider the usage of terrifying weapons, such as the Genesis device or the founder retrovirus.

It must deal with ‘classically complex’ ethical issues such as genetic alteration, machine autonomy, and so on.

The Federation holds its values – human values – as primary and imposes them on others where possible.

War for the federation is never justified. It does not attempt to remove governments it find distasteful and only fights defensively.

And so on.

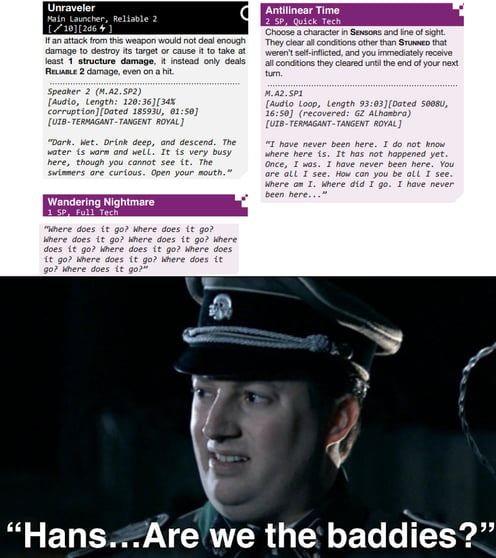

Lancer’s Union does not satisfactorily seem to confront such concerns. Worse, Lancer’s tone, design, and themes immediately result thrown into morally questionable conundrums: are the enemy heinous, or not? Are we justified in our violence, or not? Are we supposed to feel okay using these terrible weapons that do terrible things to people?

The answer to those is supposed to be in the design of the game and what is expressed by the writers in tone, though this creates a dissonance. The basic architecture of Lancer, despite the structure of the setting, seems to be not deal with the above in any satisfying way that makes the reader feel appropriate embodied.

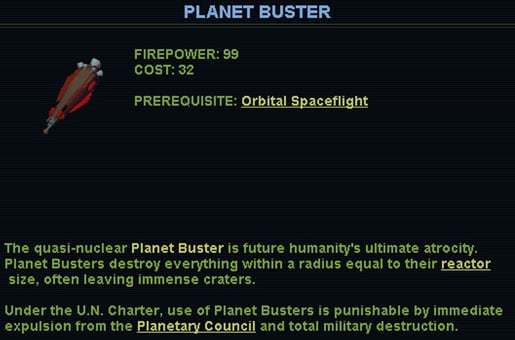

The green light and the author’s ‘OK’ is not small when terrible weapons are used or possibly used. Some games say yes to the above—and more--and do not punish the player, others are less favorable to the player and punish them, or force changes their character in exchange for this or that action. This is a matter of tone, but also of design: if the players have access to nuclear armaments or a gun that turns people inside out they might use them.

This is not to speak ill of Lancer – this merely references it as an example. It’s not easy to do what Lancer tried, and even the leading lights of more optimistic science fiction fall flat – constantly – when actual moral questions come to blows.

Walking this back, if the game responds and how we interpret the tone of the setting and the themes controls how inclined the players are to blow up a city block, or, if they care. Spire characters might not care, as their enemies in the aelfir are beyond the pale brutal occupiers who kill, exploit, and abuse them with any response – no matter how heinous – is justified. This is a real questions when one sets out to anchor a game’s basic thematic elements, tone, and so on. This also illustrates why, at least I think, utopian settings are so much more rare, and they often aren’t often written – among other reasons.

What Are We Doing?

If the setting is a utopia there’s certain standards of conduct to keep it that way – to be a monster in Sir Thomas Moore’s Utopia is to be an aberration – although, interestingly, even in the original Utopia there was assumed to be a vast underclass of Morlock-like creatures that keep the entire city-stay afloat (The helots are hidden, of course).

How players will act is not obvious, even within this framework provided by the GM. However, the tub is meant to act as a reference and give the players an awareness of how they should act. In utopia it is not clear how average people should act and their relationship to it isn’t clear because a utopia has never been seen, lived in, understood. Barbarism, cruelty, and hatred? There are plenty of examples, plenty of instructive cruelties that one might reference ad-nauseum. Stories about utopias, comparatively, difficult. Difficult to write, difficult to conceptualize, and difficult to visualize.

Humans are social things. They learn most from others and in particular how to act from others – but when there is no cue how to act they will default to what they know, what is socially convenient, or what they have been trained to do.

The players are the same, it is true, though in a TTRPG bathtub they are allowed to explore. The problem I think is that absent direction and absent any overarching principles the players will be rudderless and act in ways that are hard to make cogent, don’t feel sensible, or feel discontent with the setting in question. Worse, it can allow them to destroy their own fun and sense of themselves without the GM lifting a finger – it was the designer’s error, or the downstream effect of decisions made.

Indeed, boundaries exist, and the boundaries are defined to produce or encourage an experience the designer hopes to achieve – at least in addition to mechanics and other game features, naturally. This is very much the tub mentioned previously, but also what the players interpret as their role.

This is what I have tried to consider in design. It’s not easy!

“'Are we shooting?' 'What?' 'Are we shooting people or what?' 'What’s the answer?' 'I don’t know', that’s what I’m trying to find out.' – Three Kings, 1999

A less subtle guideline from Sid Meier's Alpha Centauri

© Austere Patio Games, 2024. All rights reserved.